We create traditional Kashubian ceramics available on the spot and offers the opportunity to visit the workshop and learn about the history of the Necel family, as well as a clay workshop.

Using Traditional Pottery as a Tool for Reviving Local Identity

Introduction

A small village of Chmielno lies in the northern part of Poland in the one of the kind region of Kaszuby. The region is known not only for its rich nature but also for cultural heritage that makes it unique in the country: the cultural group living there have its own regional language (it received its specific number in 2003 and thus discussions that were going on since the beginning of the twentieth century whether it is a separate language or a dialect of Polish were ended).

The region is also famous for its specific food (that blends sweet and sour tastes), traditional dress and dances and the most commonly known embroidery. The people of Kaszuby are also well known in Poland for their honesty, integrity and are considered to be very good workers. They consider themselves Polish with the strong regional Kaszubian identity.

Chmielno village is called “the little pearl of Kaszuby” – it lies between lakes and forests and draws many tourists that are looking for unspoiled nature and kind hosts.

The last hundred and sixteen years of development of the village is closely connected with the Necel family that consists of ten generations of potters. Their influence on cultural identity of the local people is undoubted and has interesting consequences.

The Workshop

The workshop of the Necel family is situated in the middle of Chmielno. Two-story building consists of the pottery museum on the top level, the workshop on the middle one and the huge pottery furnace on the ground level. There is also a small shop, where the Necel unique pottery is sold. The workshop produce many different kinds of clay vessels: jugs, jars, flower pots, pots with lids, bowls of all sizes and shapes, plates, twin-vessels and many more. All of these can be created for special order and shipped all over the world.

History

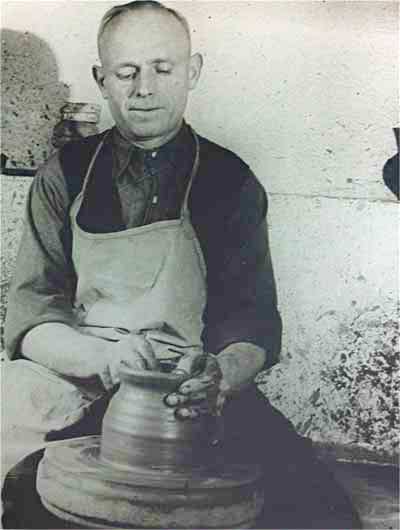

The Necel family came to Chmielno in 1897 from other small town in Kaszuby mostly for economic reasons. Poland was under partition at the time and life was hard. Chmielno was famous for its numerous pottery workshops producing vessels for everyday use, so many people from the area were looking for placing their business there. Franciszek Necel wanted to gain more experience working with famous potters in the village. Soon he became one of the best potters in the area and set his own workshop.

The vessels produced in Chmielno were plain, not decorated. The main changes that Franciszek Necel introduced to the region were connected with his father’s traditions of decorating pottery with unique patterns. After World War II the workshop became known for decorated pottery. Production of plain, undecorated utensils were gradually reduced and soon traditional patterns, not known in Chmielno before, became its trademark and main attraction.

The Necel’s workshop was visited at the time by many ethnographers and government officials including the visit of Stanisław Wojciechowski, the President of Poland in 1923.

Franciszek Necel transferred his knowledge and his skill onto his son, Leon and the latter soon took the family’s tradition into new artistic level. Leon Necel, who was the eighth generation of potters, became known especially for huge jugs, over one meter high that were richly decorated. It was the time between the two world wars and Leon Necel was then the only potter left in the village.

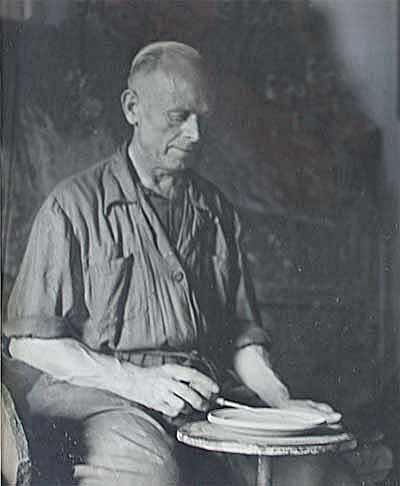

Soon the II World War begun. The potter had to close his workshop and undertake other occupations far away from Kaszuby. When he came back to Chmielno he found his workshop in ruin and started to rebuild it. The regular work started in 1946. Soon the socialism came and Necel found himself in cooperative and his wares started to lose their traditional characteristics.

Under the supervision of the governmental agency for folklore affairs he tried to keep his family’s pottery style and as it turned out the folklore pottery was in fashion at the time. The governmental agency built new pottery furnace in Necel’s workshop and few people were hired to help. The biggest problem was that the family was no longer an owner of their workshop: it was nationalized and Leon was hired to work on his former property.

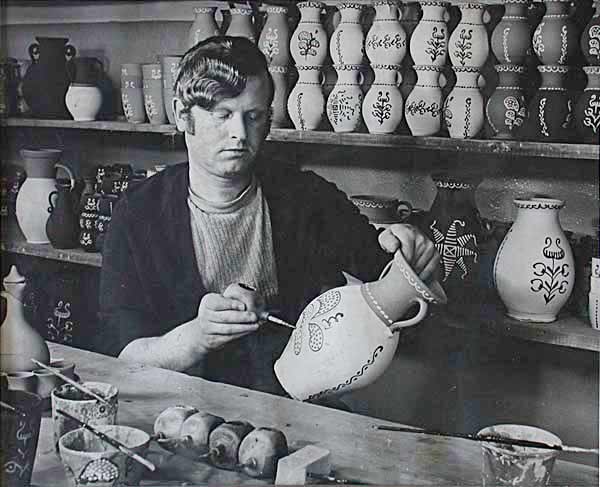

It changed as late as 1979, after 29 years. Leon’s son, Ryszard, who became his heir, got the ownership of the workshop back and continued the long family traditions in creating pottery. He was the representative of the ninth generation of potters and one of the best. He used to compare the clay vessels’ art to handwriting: in his opinion every potter has his own unique style that can be recognized as easily as handwriting. His own style was distinctive and much praised.

1993 was significant year as a local Kaszubian organization decided to help the Necel family to create the small museum in their workshop. Over 300 pieces of Necel pottery was collected and put onto display at the top level of their house.

Ryszard Necel IX did not leave any heir of his, so few years before his death his nephew started to learn pottery. And soon, in 1996, Karol Elas, the nephew of Ryszard, took the Necel family name (after his mother) and became the potter of the tenth generation in Kaszuby. The Necel family is regarded in Kaszuby as “the dynasty from Chmielno”.

The style

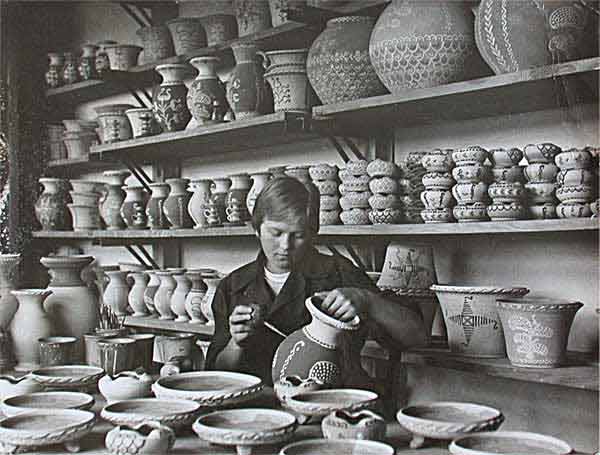

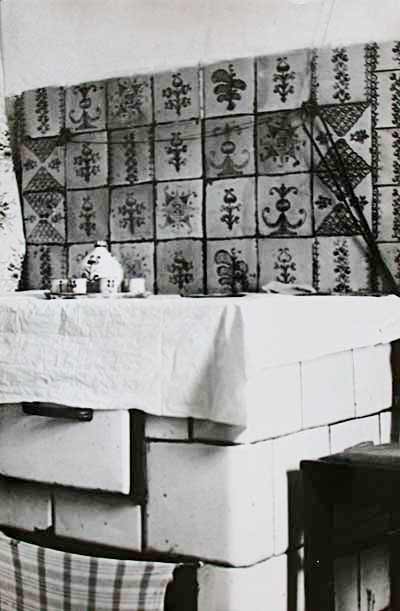

The style of the Necel pottery stands apart from all other pottery in Poland, regional or national and this is due to unique decorating patterns. There are seven patterns that are being used and they did not change at least for the last 150 years. They are being used in different combinations and are widely recognized as Kaszubian pottery decorations.

Contemporary challenges

The workshop is self-funding and at the moment there is no external help. Due to hard economic situation the family tries to get many orders for the pottery, not all of them demanding artistic skill – restaurants order special clay containers for cooking and serving food and some organizations order the clay vessels as gifts for special occasions. The family lives off the workshop thus any order is welcomed and prepared with great care.

Several new shapes were added during last years: a piggy bank, an ikebana, an ashtray and few others. Some of them are still traditionally decorated and some are left without the pattern or the glaze (this is the case of the piggy bank as the potter decided it would look silly with some painted flowers on it). Thus the workshop keeps the traditions and makes the same shapes as for last 100 years but also tries to adjust to the contemporary market. The vessels sold at the small shop by the workshop are mostly these with seven decorations.

Tourists and officials who come to Chmielno look for the traditional pottery and expect it to be what it was for last decades. And they are satisfied to find it exactly as they expected: colorful, glazed, decorated with flowers, fish scales and stars. This traditional part is being carefully kept and cherished. There is not much need for recreating the traditional pottery as it was constantly made and continued, thus today it is enough just to keep it around.

Nonetheless new ideas are being put to work and on new fashionable containers the traditional patterns are put hence there are ikebana containers decorated with fish scales, ashtrays with the tulips or elegant, delicate coffee cup with lily pattern. The older tradition is used to fulfill new ideas and new needs and it does not interfere with the shapes and patterns that came from the history of the family.

The community

The village counts 1580 inhabitants and most of them culturally define themselves as Kaszebi. They speak the regional language and are proud of their cultural identity. As mentioned before, Kaszebi are regarded in Poland as honest and good people as well as stubborn and at some point the latter is the reason why they survived all historic events and maintained their culture. Today they willingly talk about their culture and their local affairs.

They highly value the Necel family’s art and regard it as the integral part of their village heritage. One hundred and sixteen years since Franciszek Necel came to Chmielno are not exactly counted by his later neighbours – local people clearly state that “Necel is ours and always was”, “Necel’s pottery is Chmielno’s own heritage” and so on. The art that came from other small Kaszubian town influenced not only the traditions of the local culture but also the identity of the people. Some of them were surprised at my questions about the potters and their cultural affiliation as something so obvious and clear should not be questioned. Of course, everybody know where the Necel’s workshop is and how to get there and what they do in there. Everybody also talk about the family’s history and stories.

Also, everybody in the village consider Necel’s pottery as Kaszubian pottery – it comes from deep traditions and is the local trademark.

The workshop organizes the pottery classes for all who want to learn: tourists, guests as well as local people. Learning the skill comes with gaining knowledge about Kaszubian heritage and language. This is one of the ways the Necel family strengthen and spread the local cultural values.

The uniqueness

The most interesting thing is the seven patterns that are used on the vessels for decoration. The group consists of a little and a big tulip, fish scales, a Kaszubian star, a lily, a lilac’s twig and a wreath. Some of the patterns in different shapes are common in the Kaszubian culture (mostly the tulips) – they are used in embroidery, paintings on glass and on furniture’s carvings, nevertheless some of them are unique and not used anywhere else. To understand what does it mean in Kaszubian culture and why it is fascinating that people consider these patterns as purely Kaszubian, few words have to be written about other Kaszubian handicraft – the best known and widely appreciated embroidery.

Kashubian region is best known in Poland for their women who can embroider specific patterns that are unique for this region of Poland. The embroidery has strict rules that apply to shapes and colors – only pre-set shapes and only seven colors of threads can be used (including three shades of blue). The problem with this beautiful handicraft is that it was practically artificially created in the beginning of the twentieth century. Local embroidery almost completely disappeared in nineteenth century – some of the patterns were left on women’s very old wedding bonnets.

They were only gold in color and did not follow very strict rules. There were some nuns and cultural activists that thought the embroidery should be revived but they also went one step further: they created sets of patterns that were used for embroidery since. The patterns are very well known in Poland and used on many different folklore-inspired products.

Polish people may not know where exactly the Kaszuby region is on the map of Poland but they do recognize the Kaszubian embroidery as there is none other that look even closely similar to it. And the patterns for artificially created handicraft became the Kaszubian trademark in Poland as well as in Kaszuby. Women making the patterns believe that they follow some old traditions and that their grandmothers were using the same seven colors and patterns of flowers, twigs and leaves.

The very short story of Kaszubian embroidery shows the uniqueness of the Necel pottery’s decorations that actually come from the past and thus rightly are regarded as deeply and traditionally Kaszubian. The only puzzling thing is that local people stress that nobody else is using these patterns for anything else. The patterns are not used for paintings, carvings or any other craft. What is more, people in Chmielno emphasize that the seven patterns belong to the Necel family, that they are their own.

The Necel pottery patterns are Kaszubian, come from deep regional traditions and are in a way much more “real” than the ones used on embroidery and at the same time due to some history twists they belong to one family and are used only on pottery. Their origin is not clear. Franciszek Necel, who came to Chmielno in 1897, was decorating his vessels with the patterns he remembered from his father’s pottery work in the other part of the region.

They could have been used by other potters also, but there is no evidence for this as most of the local pottery was destroyed during the second World War and no other pottery workshop is left there. The patterns were handed down from father to son for four generations and they are the only patterns of the kind left in the region. As mentioned before, there are no other traditional pottery workshops left in the area so there is no possibility to compare the pottery traditions. The Necel pottery is called “the last Kaszubian pottery in the region”.

It is very interesting how probably the last purely traditional patterns became the exclusive property of one small family and at the same time are regarded as “Kaszubian” in every aspect.

Aleksandra Wierucka

Department for Cultural Studies

University of Gdansk, Poland